Before they were migrants, they were people.

At the conference (link in Danish) in Odense on May 12th, Global conflicts – local challenges, New citizens, training and workplace integration, there was an economic overview.

At the conference (link in Danish) in Odense on May 12th, Global conflicts – local challenges, New citizens, training and workplace integration, there was an economic overview.

You would expect the children of migrants to do better than their parents. They should learn Danish as their first language and therefore be much more ready to take their place in the labour force. But counter intuitively, it turns out that the children of migrants from non-European countries do worse than their parents in spite of their language advantage. Migrants and their children have a higher percentage of self-employment than native Danes but this is concentrated into a few stereotypical industries such as taxi driving and pizza parlours and is likely born of desperation and reliance on family and ethnic networks rather than any raised desire to be self-employed. This also spills over into informal and illegal spheres.

Therefore a facility with the language is not a sufficient condition to doing well in Denmark. The suspicion falls on culture and identity as a reason for this result. Shahamak Rezaei from Roskilde University took us through some of his findings.

Economists base most of their theories on the assumption that people act rationally, in their own self-interest, but cultural differences could lead to different rational decisions.

If you are looking at supplying a country’s labour force then it is cheaper to import young people and support them for three years or so until they can enter the workforce than to support them from childhood as happens with the native-born. In fact this is happening in the UK in the migration debate which is part of the wider EU referendum campaign. Those who complain about high levels of migration should support more training opportunities at home so that the UK does not simply import ready-trained workers.

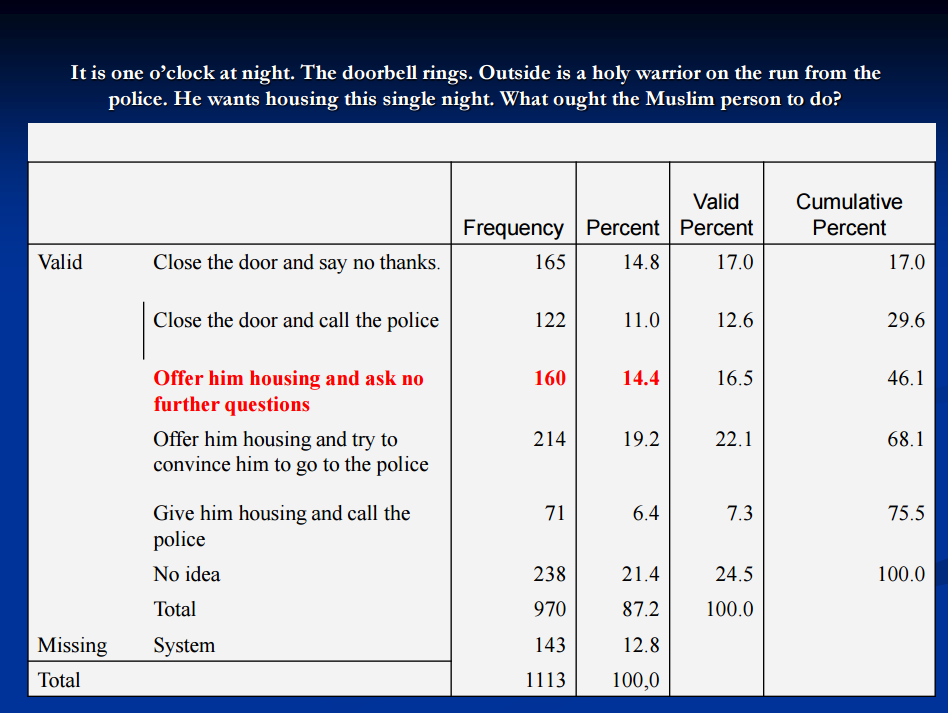

In Denmark, one can’t argue that people lack training. So the only variable left is that of cultural identity. This was tested through a rather chilling exercise in which a sample of second generation migrants were asked what they would do if a person of their own ethnic heritage, but unknown to them, knocked on the door and asked for shelter for one night after committing a terrorist act. The options they were given included:

- Refuse them entry

- Invite them in and try and persuade them to give themselves up to the police

- Invite them in and secretly contact the police

- Give them shelter and ask no questions

The worrying result was that 14% of respondents chose the last option. And this highlights the disconnect between second generation non-Western immigrants and their host country (see all results below).

Danish + work + tax ≠ Integration

Rezaei saw this as an indication that inclusion rather than integration should be the goal and proposed that we should be looking for answers in positive sociology and transnational entrepreneurship.